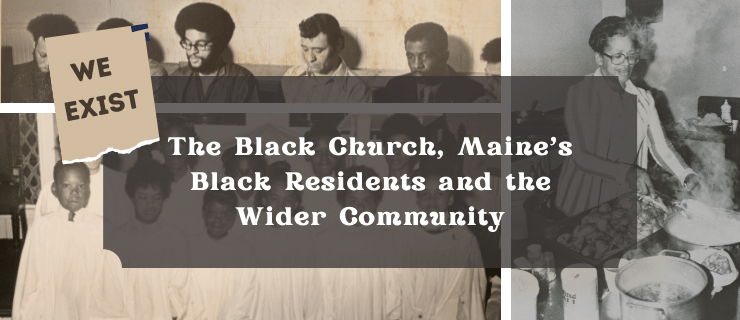

Series 3: The Black Church, Maine’s Black Residents and the Wider Community

"We Exist: The Black Church, Maine’s Black residents and the wider Community" is the third of the six-part digital exhibit series. The current exhibit explores the various relationships between Black parishioners and the Black church, and the community at large. The explorations of the relationships between Maine’s Black residents and the Black church encapsulate in miniature the characteristic qualities of the relationships that Maine’s Black residents have with the Maine community.(1)The exhibit is comprised of photos, written transcripts, and audio interview clips from the Gerald E. Talbot and African American Collections. The exhibit centers on Black families and individuals in the state of Maine and seek to tell their stories of how the Black church has helped them in their personal, civic, financial, and political lives.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Religious organizations have been identified by many researchers to be the greatest institutions through which African Americans, individually and collectively, are spiritually, psychologically, emotionally, and physically enhanced.(2,3,4) The Black church is more than a religious institution; it is also a social movement and a social organization(5) and is very responsive towards the needs of its community members.

The Black church and the Black family are two of three of the most critical institutions whose interactions have been responsible for the viability of the African American community. (6,7) And much like the Black family, the Black church underscores the most basic values of the African American cultural heritage. These values include spirituality, high achievement aspirations, and commitment to family as "enduring, flexible and adaptive functional mechanisms for survival." (8) The Black church as a uniquely Black-directed institution has historically been called on to serve the religious/spiritual,(9) educational, political, and even the economic needs of its parishioners. The Black church was frequently the only place that African Americans could gather without being supervised or relegated to a subordinate position.(10) Studies suggest that the Black church plays a critical role in the lives of parishioners and the wider community as civil society.(11,12,13) In addition to serving its principal role as a religious institution, the Black church helps parishioners and the community, maintain their spiritual lives.(14) History records that the Abyssinian served as the meeting site of various social groups, including a sewing circle, temperance society, and antislavery society. The Black church also served the educational needs of the Black community by serving as a school for local Black children. The Abyssinian played an important part of the larger Colored Convention Movement (1830-1861), a movement that saw Blacks gather in major American centers to discuss issues of concern to them, one of the most pronounced of these topics having been the abolition of slavery (pg. 10). Green Memorial in Portland flexed its entrepreneurial muscles by participating in the sale of cooked meals to fund the church’s mortgage and campaign fund raising. At times, sale proceeds supplemented the church’s budget.(15)

Over the years, an undeniable and convincing body of evidence has emphasized the importance of African-American churches as conduits for political skills, resources, and mobilization.(16) There is indication of the continuing importance and durability of the African-American church as a viable and politically relevant institution.(17) Historically, African Americans who consistently attend church belong to a larger number of politically relevant organizations. (18),(19) Of note, simply attending church does not provide enough social capital resources to push African Americans into political engagements. Rather, it is observed that Black churches that espouse a civic culture where members are exposed to political discussions and are encouraged into activism, (20) at times by church leaders, (21) and push African American parishioners into political engagement. Involvement in church committee life is important to Black civic skill development (e.g., communication, writing, and organizing skills), which increases these church activists' competence and confidence to participate in political activities. (22) We hope that these photos, written word, and audio add to our quest to adequately examine the relationships that exist with Black residents in Maine and the Black church.

The exhibit consists of three focal galleries. The first gallery consists of photos which capture Black inhabitants in Maine participating in church activities both inside and outside of the church. The second and third galleries consist of interview quotes and selected audio recording clips from the oral history project "’Home Is Where I Make It’: African American Community and Activism in Greater Portland, Maine". The visual and audio presentations will help those with certain disabilities who are interested in the exhibit to actively participate. Next, the use of multiple sources (photos; written word; audio) helps to support observable results regarding Black residents in Maine and their participation in various church activities. The quotes and audio clips are representations of how Maine’s Black residents talk about the creation of church denomination across Maine, how these residents view the church as an integral aspect of their economic, political, cultural, and spiritual lives, and the impact of the church has on the wider community as civil society.

We are indebted to our partners at the Osher Map Library (OML), University of Southern Maine (USM) Special Collections, and University of Southern Maine Libraries for their support in digitizing and building the exhibit site. This site was built by USM Libraries Digital Commons and Digital Projects and OML staff members: Mary Holt (Digital Projects Manager) coordinator for the USM Digital Commons, construction and organization of the exhibit; Carrie Bell-Hoerth (Library Specialist in Digital Projects and Access Services with USM Libraries) assisted with uploads and formatting. Special thanks and gratitude are in order for Susie Bock (Coordinator of USM Special Collections and Director of the Jean Byers Sampson Center for Diversity in Maine) David Nutty (Director of Libraries and University Librarian), and Libby Bischof, Executive Director of the OML. Dr. Lance Gibbs served as the research lead for the project, providing historical background from news and scholarly references, and authoring the short contextual catalogue essay entries which complement the photos, written, and audio galleries.

We hope the digital exhibit transmits to wide and diverse audience who may not have otherwise engage with this aspect of Maine’s history. Also, we hope the exhibit serves as a guide for other institutions to follow that want to engage in the larger discussion on Black inhabitants relaying their histories through their own voices.

View References

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.